Colliery Checks: An Introduction

Although the literature of paranumismatica is meagre when compared with its elder brother numismatics, I have found a strange omission on the theme of colliery checks. Coal mining tokens are quite well represented in specialised books, and extend back to the 17th Century with one example from Yorkshire for ½d "For the use of ye cole pits." (Whiting, 1971, p.52). However, the later mining checks of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries have more are less been neglected. As few mines currently survive, these items are now artifacts of our Industrial Heritage and, like other types of token, are eminently collectable. Each check, like a token, has its place within the social milieu. The strong localised communities that were formed during the development of the coal mining industry are the subject of many sociopolitical studies.

This article which was written during my residency in South Wales, and in consequence has some bias to that area, sets out to try and redress the omissions of many earlier general token studies by introducing the vast series of British mining checks that have emanated since the 1860's and 70's.

In 1935 the number of working coalmines in the country, both commercial and private, was approximately 1,600. The private mines were usually small, with up to 100 workers. As an extreme example, Coed Caer, nr. Abergavenny employed only one person below ground and one above, raising 70 tons of coal per annum. But at their peak of performance in the 1920’s and early 1930’s a number of collieries employed nearly three thousand staff. Ashington Colliery, Newcastle-on-Tyne employed over five thousand workers.

Collieries had the usual offices with specialised buildings such as Lamp Rooms, electrical sub-stations, mechanical workshops, saw mill and carpenter’s shops, pithead baths, coal preparation plants and railway sidings. In addition, a number of collieries had coking ovens developed from the 1870’s that had capacity for gaseous by-product recovery. For example from 1936 Bolsover Colliery near Chesterfield was to become the manufacturing centre for "Coalite" smokeless domestic fuel. In addition the works also produced other important by-products, such as tar, sulphate of ammonia, benzol and naphtha. During the war many such by-product plants were to provide yet another important national role with the R.A.F. fueling 20 squadrons on coal petrol that was ‘cracked’ from coal-oil.

At the commencement of nationalisation in 1947 the number of collieries in Britain had dropped slightly to around 1,500 of which 500 were private mines. In 1985 South Wales had only 28 collieries open, compared to some 200 commercial collieries and 100 private mines working in 1947.

Today, following privatisation, Wales has only one privately owned deep mine (Tower Colliery) other than opencast workings, and there are less than 100 small private drifts and levels mines.

Figure 1: Two pre 1947 lamp tokens. LEFT - A brass lamp check issued by the Fife Coal Company for use at their Comrie Colliery, Scotland. RIGHT - A copper lamp check used at Haig Colliery, West Cumbria.

When first employed at a pre 1947 colliery, each miner was issued with a lamp check. Originally used in about the mid to late 1800’s solely as a lamp receipt and a booking in and out for work, it later became part of a general safety checking procedure. An identification number on the check was personal to each miner, and corresponded to the number on his lamp. This number was usually added as a counter mark at the colliery; but in later (post 1947) years some collieries had the facilities necessary to add their own incuse numbers serially from 0001 using a numbering machine.

Figure 2: Two colliery checks from Goldthorpe Colliery, South Yorkshire. The one on the left, issued in the name of the British Coal Corporation, has the normal hand stamped identification number. The one on the right, issued by the National Coal Board, bears machine stamped serial numbers.

One result of the far reaching Coal Mines Act of 1911 was to make the Colliery Manager officially responsible for the recording of the number of persons going below ground and returning from below ground daily. If required by the manager, the miner had also to record his presence thus in accordance with a system approved by the inspector of the division (General Regulation No 30). This regulation was the start of tighter checking controls involving more than just a single lamp token.

Lamp checks were usually round and made of brass. Normally they were embossed or incusely stamped with both the Coal Company's name plus that of the Colliery at which they were used. In many of the earliest checking systems it was quite usual for this lamp check to be taken home by the miner, and then exchanged for a lamp when commencing his shift. However, from the early 1920’s and prior to nationalisation in 1947 variations both in the shape of the checks and the materials of their manufacture can be noted. Both zinc and aluminium were frequently used and to a much lesser extent copper, plastics and even steel. However, following an explosion at Glyncorrwg Colliery in 1954, aluminium at the coalface was prohibited. The official report on an explosion at Six Bells Colliery in 1960 recommended that the area of restriction be extended. After 1962 aluminium was not used, as it was considered unsafe; in friction with rusted steel it could produce incendiary sparks. This enables us to determine to some extent the latest issue date for aluminium checks which have the N.C.B. inscription. It has been considered that aluminium checks were more often issued during the war years due to a shortage of brass.

Lamp checks issued prior to 1947 that had the Company name embossed on them were generally more ornate in design that later issues. Laurel wreaths, ornaments and beaded borders were the rule rather than the exception. After 1947 issues of checks became increasingly more plain and uniface. An example of one of the latter sterile check designs can be found in the post 1965 issue of Wyndham/Western Colliery that is stark in its simplicity.

Figure 3: LEFT - A pre 1947 brass lamp check issued by the Ocean Coal Company Ltd. for use at its Western Pits. RIGHT - A late N.C.B. brass colliery check issued for the combined Wyndham/Western Colliery. Note the relatively sterile appearance of the N.C.B. issue compared to the much earlier and more artistic pre 1947 issue.

The most surprising aspect when commencing to collect mining checks, is the measure of diversity. As well as differing materials, patterns of checks range from large rectangular to square; from round and ‘polo’ type to ¼ clipped round; from oval to oblong; from hexagonal to octagonal; from less than 25mm to more than 50mm. There was some appearance towards standardisation following N.C.B. ownership, but differences still remained. On some later checks the name of the colliery was abbreviated to initials which, although adequate for the original use, can today give rise to identification problems.

The actual safety checking/tallying procedures used from the time the miner commenced his shift varied - sometimes quite considerably - between collieries. A detailed survey of UK checking procedures is currently being undertaken via the "Forum Page" of the National Mining Memorabilia Association's web site. Hopefully this survey will yield some interesting results in the near future. In their earliest forms the checking procedures employed at most collieries consisted only a single lamp check. Systems comprising two and then a three checks were to follow in much later years. In the earliest and most basic systems, the miner exchanged his lamp check for a numbered lamp in the colliery's lamp room. The check, after the number had been entered (colour coded for each shift) on a Daily Record Sheet, would then be hung on a large numbered board until the lamp was returned at the end of the miner’s shift. A second check was introduced in the early 1900’s (Edge, 1991), but many collieries found this still to be insufficient. As an additional safety measure a three-check system was introduced later in the South Wales, coming into general use within that particular coalfield by the 1970’s. This system comprised a round lamp check plus two additional "man power" checks which were usually oval and oblong respectively, although theses later two smaller checks could sometimes small round and square. The main criterion was for ease of recognition. All issued checks had the name of the colliery together with a number, individual to each set of two or three checks. Colliery Training Centres had their own checks.

Under the National Coal Board (1947 onwards) the issue of checks was put under the control of the Foreman Lampman, who was responsible to the Lamp Inspector at the Colliery Offices, and the Colliery Manager. Further up the hierarchy was the Area Lamp Inspector and Area Production Manager. As those persons kept a close eye on expenditure, checks were therefore used more than once (i.e. renumbered), if possible. A digit or two could be chiselled or ground out, or the whole number soldered over and renumbered, or numbered on the reverse of the check. That is the reason for some checks showing traces of solder over a number; it has been scraped off by an enquiring collector - an unnecessary action that irritates the purists. When a colliery's stock of checks was getting low, due to loss, damage or the employment of new staff, a further supply would be ordered having regard to comparative costs between manufacturers. The shape of the checks, particularly the lamp checks, could change at that time. Most collieries ordered their checks from the firms that supplied them with their safety lamps. In South Wales, Thomas & Williams of Aberdare supplied some 600 collieries. In England, Ackroyd & Best of Leeds and A.J. Gilbert of Birmingham were amongst the suppliers.

After nationalisation of the British coal industry in 1947 most manufactured lamp checks were inscribed with N.C.B.. Those made prior to 1947 and still in use, often had N.C.B. added as a counter mark. Later issues, particularly in South Wales, may have omitted the N.C.B. but had the initials of one of the eight Coal Board Divisions, e.g. S.W.Div. (South-Western) which covered South Wales, the Forest of Dean and Somerset. After 1948 the seven N.C.B. Area boundaries in South Wales were redrawn. In 1957 the N.C.B. had 51 Areas within its eight Divisions. Due to organisational difficulties and continuing pit closures, those eight Divisions (which had declined to 35 Areas by 1966) were gradually restructured down to 13 Areas, losing the administrative Divisional tier. Scotland became a unified Area in 1972, and South Wales in 1973 amalgamating its previous seven Areas. Checks struck after this date may have the S.W. (for South Wales) embossed on them, omitting the previous ‘Div.’ Or Area numbers. This applied to all other parts of the country, so that in 1975 for example, the South-Eastern Division (Kent) became part of the South Midlands Area, and by 1982 the North-Western Division together with the West-Midland Division become the Western Area.

From 1987 the National Coal Board was renamed the British Coal Corporation, consequently most checks struck after that date had the initials B.C.C. in their legends. Now, since re-privatisation of the British Coal industry on 30 December 1994 collieries have new owners, or operators under lease and licensed from The Coal Authority. Only a handful of new checks were to be struck by these new colliery operators as by the early 1990s the use of checks became at first supplemented and then totally replaced at most pits by the alternative use of magnetic swipe cards. It is this new electronic based checking system that is current in all of the remaining mines operated by UK Coal Ltd. (formerly RJB Deep Mines). Perhaps in time these swipe cards will become as collectable as British Telecom Phone cards!

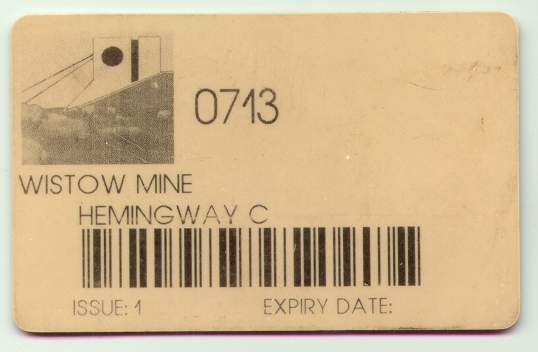

Figure

4: An electronic swipe card issued by RJB (Deep Mines) for use by Mr. Charles Hemingway at Wistow Colliery (part of the Selby Complex, North Yorkshire).In addition to checks being use as a form of lamp issuing receipt and as part of safety checking procedures they have had many additional uses within the British coal industry since the mid to late 1800s. Some of the additional types of check which are commonly encountered by collectors are described below.

Time Checks - Before time clocks were in service in the late 1940’s to early 1950’s a brass, or other type metal check was used in some collieries. These were often inscribed TIME CHECK or TIME TICKET and bore a countermarked identification number. They were collected and hung on a tally board at the commencement of each shift. Other collieries relied on the lamp check and regular inspection of check boards to determine who was leaving work early or working overtime.

Figure 5: Two colliery time checks. LEFT - A pre 1947 brass issue from Wheldale Colliery, North Yorkshire. RIGHT - An N.C.B. brass "Dotto" check from either the National or Lady Windsor Colliery, South Wales.

An alternative time checking system known as ‘Dotto’ was introduced in 1961 at the National Colliery, Wattstown, near Porth, South Wales. Brass, 41mm diameter round checks with plain edges and flat rims were issued. After being posted in a slot of a special check reading machine, a series of holes (corresponding to numbers) in varying positions on the check ensured the check acted in a manner similar to a punched card system, ending up on an appropriate set of pins. Information on this system is sketchy. It was thought that contact with the pins caused a bulb to light next to the miner’s name in the Lamp room. Additionally, or alternatively, a note of the time was sent to the Colliery manager’s office by a form of ticker-tape machine. Although the "Dotto" checking system was introduced at several South Wales collieries it was eventually abandoned at all of them.

Pay Checks - In parts of South Wales these identification checks were drawn from the wages office on a Thursday, prior to the Friday payday. They would then be exchanged for a pay slip, and the wages paid on signature. In many other coalfields where pay checks were in use they were often issued to each miner at the start of his employment and retained by him for the rest of his working life at the pit.

Figure 6: Three totally different designs of colliery pay checks. LEFT - A brass issue from the N.C.B.'s Grassmoor Colliery Training Centre, North Derbyshire. CENTRE - Possibly a pre 1947 steel and blue enamelled check with a highly convex surface from Whitwick Colliery, Leicestershire. RIGHT - An early N.C.B. brass issue from Water Haigh Colliery, North Yorkshire.

Shot Firing Tallies - The size of a round lamp check, these were used in the S.W. Division of the N.C.B. as authorisation to act as a sentry in an area where shot firing was taking place. Similar but usually much larger brass and plastic checks were used in other N.C.B. Divisions, often bearing the word "SENTRY" on them.

Figure 7: Two shot firing sentry checks. LEFT - A standard brass type used throughout the South Wales Coalfield. RIGHT - A much larger brass check from the combined N.C.B. Goldthorpe/Highgate Colliery, South Yorkshire.

Canteen Tokens - If the miner was required to work extra hours, he was entitled to refreshment after every two hours. The payment for such free canteen meals would take the form of a numbered check, tokens bearing varying monetary denominations or stipulating that they were "good for" a certain type of meal or beverage. In later years authorisation for free meals would take the form of a paper chit, exchangeable at the pit canteen for the equivalent amount stated.

Figure 8: Three different types of colliery canteen tokens. LEFT - An aluminium check used at N.C.B. Donisthorpe Colliery, Leicestershire. CENTRE - A green plastic token from Elsecar Main Colliery, South Yorkshire. RIGHT - A brass canteen token of 1/- denomination from Lewis Merthyr Colliery, South Wales.

Pit Head Baths Tokens - Where available after the 1920s these were used freely by the miners after each shift, although they had to pay for the use of the colliery’s soap and towel unless they provided their own. The baths could be used also by contractors who often used tokens to purchase their soap and a towels from the colliery bath’s attendant. Such tokens were either purchased in advance by, or charged to each respective contracting company (see also Cox & Cox nos. 141-148).

Figure 9: Examples of a pit head baths token & identification pass. LEFT - A pre 1947 aluminium baths token of 3d denomination from New Lount Colliery, Leicestershire. RIGHT - Possibly a pre 1947 or early N.C.B. baths entry pass (?) from Lewis Merthyr Colliery, South Wales.

Duplicate & Replacement Checks - Before all checks were kept in the Colliery Lamp room many miners inevitably lost or mislaid their lamp checks. A duplicate would then be issued on a temporary basis. This would be a plain brass blank of the required shape with the number and sometimes the name of the colliery in countermark. It was also common in some areas, such as South Wales, for old or redundant checks to be issued as replacements. In such cases their old identification number would be soldered over and a new one stamped in its place.

Figure 10: A brass re-used colliery check from N.C.B. Blaenant Colliery, South Wales. Note the use of solder to mask the check's previous identification number.

Coloured Plastic Checks - A three-colour check system was used in some collieries, where a self-service method was operational in the Lamp room. This system commenced in 1936 for battery-charged electric lamps, but was slow to develop. By 1947 only some 85 collieries had adopted the procedure. In that system no lamp check was issued for the miner to take home with him. A colour was allocated to a particular shift, the appropriate coloured check with the miner’s number being kept on a hook on the lamp battery-charging frame, above the lamp. Each miner would drop his check in a slot by the lamp room exit, on his way out. The Lamp room staff would then transfer all the checks from that shift to a check board kept in the Lamp room, and record them on a time sheet. When the lamps were returned at the end of the shift, the Lamp room staff replaced the checks above each lamp. Absentees or those to whom lamps were issued (including such persons as electricians) working overtime could then be noted immediately.

Figure 11: A set of three un-issued plastic colliery checks bearing the name of the well known British electric safety lamp manufacturer "OLDHAM". This set of checks was sold as part of an export order to T.I.S.C.O.'s Sijua Colliery, India.

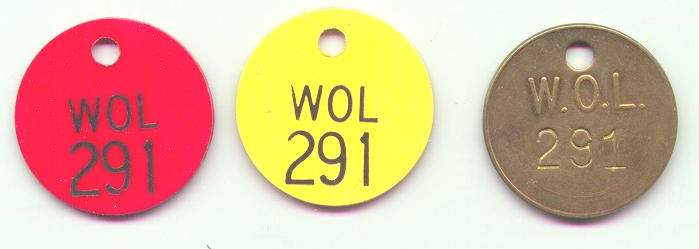

Rescue or Emergency Organisation Tallies - These rarely used checks were normally round and and existed in similarly numbered sets of three. Each set normally comprised one red and one yellow plastic check plus a third of brass or copper. A supply of these serially numbered sets was issued from the area Mine Rescue Station. Each set was sealed in an official envelope and kept in a locked box in each colliery for use by an emergency service, e.g. Mine Rescue Service in the case of explosion or other disaster. The red plastic disc would be exchanged for a lamp, the yellow plastic disc handed to the Banksman on descent into the pit, and the brass or copper disc hung round the neck. The latter would aid identification if necessary, in the case of a further incident.

Figure 12: A set of three "Emergency Organisation" tallies from Woolley Colliery, Yorkshire.

Key Fobs & Identity Tags - Areas controlled by locked doors had key tags marked appropriately. The tags were often similar to or even reused lamp checks with the relevant area or key identification information (e.g. Fan House, Front Gate, Deputy's Cabin etc.) counter marked in place of the more usual miner's identification number.

Figure 13: A standard zinc colliery check from N.C.B. Royston Drift Mine, Yorkshire. This particular example has been re-used as a key fob to access the Colliery's No.4 Shaft entrance.

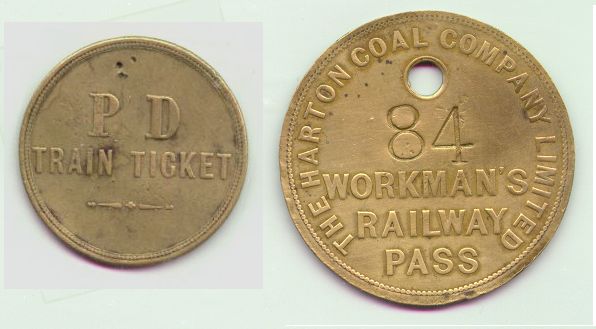

Colliery Related Passes & Tokens - From the 1890s special collier’s trains were run jointly by several colliery owners and the railway companies. Numbered checks, or more correctly metal or plastic passes, were issued to miners who used the trains (and later buses) for travelling to and from work. Cox & Cox (1994) give photographs of items from Taff Vale Railway Co., Cambrian Collieries Ltd., Cwmaman Coal Co. Ltd. and others in their section ‘Transport Tokens and Passes’, under which heading these items more strictly belong.

Figure 14: Two pre 1947 colliery workmen's brass train passes. LEFT - Issued by Powell Duffryn for use on an unspecified colliery route in South Wales. RIGHT - Issued by the Harton Colliery Company for use on its private railway line between South Shields and Whitburn Colliery, County Durham.

Miner's Association Checks or Badges - From the 1870's many of the newly formed Miners' Associations and Federations started to issue Membership badges to signify that those who wore them were loyal union men and fully paid-up members of their local miner's union branch or lodge. The shape of such badges, which were often very ornate, changed regularly to signify the advent of different lodge membership subscription periods. Such early badges normally have at least two small outer holes which were used to sew them onto their owner's jacket lapel or cap.

Figure 15: Two very different types of pre 1945 brass miners association badges/checks. LEFT - A heart shaped badge issued by the Wyndham Lodge of the South Wales Miners' Federation signifying that its original owner was a paid-up lodge member for the third quarter of the particular year of issue. RIGHT - A circular badge issued in the name of the Somersetshire Miners' Association bearing their motto "FOR UNION & FOR RIGHT".

Unissued, Restrikes & Reproduction Checks - At least one of the firms who supplied mines with checks in South Wales (E. Thomas & Williams, Aberdare) still hold the dies and will occasionally make restrikes of certain checks. They will also number single ones, if the purchaser requires it. Welsh colliery checks that are clean, still have their original matt finish and are unnumbered, may possibly be modern restrikes. However, a further and much scarcer series of un-issued checks, many of rare pre 1947 Coal Companies, first appeared on the market in the early 1970s and then again (post the 1999 Nobel Sale, Australia) in early 2000. These checks have been traced back to an ex-factory or salesman's sample stock originating from from the company of Henry Pasely & Sons of Sheffield (and later Manchester) who made colliery checks from the late 1800s to c.1952 when they finally went out of business.

Some years ago reproductions of checks were rarely seen. Unfortunately and more recently there have been a number of checks appearing on the market that on first sight appear to be used and of the appropriate age. Using modern techniques that can ‘age’ a check and give it the necessary discolouration, buyers have found out later that they have obtained a modern forgery.

At this juncture it may be appropriate to briefly discuss the current cost of purchasing colliery checks. In general, the buying price to collectors of checks approximates that of other types of contemporary tokens. Most check issues after 1947 sell in the low single to low double figure range. Checks originating prior to 1947 that bear their Company name on them normally sell for between the mid single to the lower to mid double figure range. When considering the value of any check it should be remembered that much depends on its condition, its age, whether its design is embossed or not, the size of the colliery (which can reflect on the number of checks issued) plus the time the colliery was operational etc. etc. As with any form of collectable there are therefore many variables that determine the current value of a colliery check and hence it is difficult to generalise on prices. It should also be remembered that the above quoted buying prices may be 33% to 50% higher than their market selling price to a dealer to reflect the usual range of profit margins.

Part of the great interest in collecting mining tokens is to know something of the profile of each mine represented by the individual checks. In order to find out all such necessary information and history the collector should be aware of several key references. The Colliery Year Book and Coal Trades Directory is invaluable for its list of mines, particularly in the 1920’s. Such directories list Coal Company names against the mines they owned, colliery addresses, numbers of staff employed, output details, seams worked and other invaluable information. O’Connell’s Directory (1930 series) provides similar information. Another useful work is the Guide to the Coalfields, published annually by the Colliery Guardian during the life of the N.C.B. from 1948. Additionally the positions of each mine are shown on maps scaled at ¼ inch to one mile. As these are now all collectors reference items, they are difficult to obtain. However, a selection should be available (if in a coal-mining area) on site in your Public Reference Library, or can be request from the Public Library Service. If more detailed information is required, records of mines closed prior to 1947 should be held at County Record Offices. Records from 1947 or profiles of mines should be held at Centris Coal Benefits Ltd. (c/o Archive Centre, 200 Lichfield Lane, Berry Hill, Mansfield, Nottinghamshire. NG18 4RG). In addition information on local mining areas in particular or procedures in general is usually given willingly at Mining Museums, of which there are several throughout the country. These usually have a collection of mine checks amongst their memorabilia. Many of the staff are ex-miners, who are only too pleased that visitors are interested sufficiently to quiz them. Locations of such museums can readily be found on the "Internet" or from Telephone Directories or the "Yellow Pages".

Of course, if you meet up with ex-miners, don't hesitate to ask them about their memories of the different checks and checking procedures which they have used throughout their working lives. Once this generation has gone, most of the information will have departed with them. A pause too long now may result in much of this valuable paranumismatic mining history will be lost forever!

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Gary Mason of Lewis Merthyr Colliery and Museum at the Rhondda Heritage Centre, Trehafod, and Peter Walker of the Big Pit (Pwll Mawr) and Museum, Blaenavon, for information on checking procedures. Additionally Gary Mason and Mark Smith have both provided additional information and the illustrations for this revised version of my original article.

Select Bibliography

Based on the author's original article first published in the Token Corresponding Society Bulletin Vol.5, No.8, Pages 285-294 & later by kind permission in NMMA Newsletter No.9 Spring 1998 © David Shaw 2002.

An Appeal for information to Ex-British Miners.

I would like to hear from any ex-miners who who like to contribute to our on-going survey of colliery and metal mine checking procedures. Any memories of the different types of checks used at your old mines would be most welcomed. Please reply without delay by double clicking the e-mail icon below;

Better still you can respond by via the "REPLY" facility which you will find if you double click the following hyperlink which will take you onto the appropriate part of the NMMA's on-line "Web Forum". When replying please remember to state the name of the colliery for which your information applies and the approximate dates between which you worked their.

Information about the use of pit checks required from Ex-British Miners.

Thanks in anticipation - Mark Smith.