What's the story behind this Cumbrian Mining Fob?

Commemorative Gold Fob/medal - engraved "TOWNHEAD MINE EGREMONT / MARCH 13TH TO 18TH 1913".

I would be interested if anyone can supply me with any information regarding the rather unusual 9 carat rose gold mining fob pictured above? It weighs 4.6 grammes and measures 31 mm tall by 28 mm wide. Its reverse side bears a 1912 hallmark for Birmingham plus an partly legible three lettered makers mark starting with "J" and followed possibly by an "A".

The lettering on the front of the spade reads " TOWNHEAD MINE EGREMONT" and on its reverse there are the dates "MARCH 13TH TO 18Th 1913". I assume the mine referred to was located in Egremont (Cumbria) in the United Kingdom.

REPLY No.1

Given that this fob bears a 1912 hallmark and an engraved legend mentioning the date of March 1913 I feel sure that it was originally made as a standard "off the shelf" fob or charm that was aimed at sale to someone with mining connects or interests. Given the period at which it was made such subject matter would have had an appeal to a significant proportion of Britain's working population. However, as is obvious, what probably was made for sale to a general and wide market has been customised to commemorate a specific mine and dates in history. Namely Townhead Ironstone Mine, which was located near Egremont in West Cumberland, plus the precise period March 13th to 18th 1913.

The Townhead Mining Company Limited of Egremont was formed in 1900 and operated an Ironstone Mine comprising a series of shafts north of Egremont town cemetery. By 1923 the last of these shafts had been abandoned.

Townhead Ironstone Mine, West Cumberland.

The following account (taken from the Mines Inspectors Annual Report for 1913) gives the story behind the events which are commemorated by this fob. They make particularly interesting reading.

"The most sensational accident of the year, although only one life was lost, occurred at Townhead iron ore mine (No. 7 Pit), Cumberland, and was due to an irruption of water from the old workings of a neighbouring mine abandoned over 20 years ago (i.e. Bain's No.10 Pit).

An accumulation of water was suspected in these old workings, and Mr. Leek, Inspector of Metalliferous Mines, had many conversations with the management on the subject, which resulted in the plans of these abandoned mines being obtained from the Home Office. Unfortunately few levels were inserted on the old plans, and considerable uncertainty existed as to the exact position.

About a month prior to the accident the water in the old workings was safely tapped by an inset from the shaft at a higher level specially set off for that purpose, and the head of water was thereby reduced by about 16 feet. The only place in the lower level near to the old workings was No. 5 Company's drift, the working of which was suspended and a timber dam erected therein. Five boreholes, from 5½ feet to 9 feet in depth, had previously been put in the roof of this drift, but they were all perfectly dry. From the old plans and from other information in the possession of the management, the intervening thickness between No. 5 drift and the old workings above appeared to be about 30 feet. After the accident it was found that there was a thickness of 9 feet only. Under ordinary conditions this would have been an adequate barrier, but in this case the water had gradually made a channel through soft ore and shale. The dam, which had been built as an additional safeguard, proved insufficient to prevent the water flooding the mine, owing to the fact that it had not been built far enough into the solid side of the drift, thereby allowing the water to pass through.

The inrush occurred a few minutes after 6 a.m. on the 13th March, as the men comprising the morning shift were entering the mine. Nine men had descended and were travelling along the main roads from the shaft. One man, James Ward, had left the main party and was proceeding to his work in a different direction. The others were suddenly alarmed by the rush of wind and the roar of approaching water. They immediately turned and ran back towards the shaft. One of the men, however, John Cairns, remembering that Ward had passed inbye retraced his steps and went back to warn him. When the other seven men reached the shaft they found that four more men had come down. There was then no additional water at the shaft but the cage was immediately sent up with five. Before the next cage came back a wave flooded the flat sheets up to the men's ankles and five of the remaining six made a dash for the ladder compartment. Four of them travelled up safely, but the other man, James Bewley, had got on to a short ladder leading to a haulage wheel instead of the main shaft ladder, and he was drowned. The sixth man came up on the cage alone.

The ladders in the shaft are in excellent condition; they are inclined at an easy angle and the stages are good and at frequent intervals and it was unfortunate that the short ladder should have been in such a misleading position. Cairns and Ward found their return cut off by the rising water, so they gradually made their way to the highest working where there was a 5-inch borehole, which had recently been put through from the surface. Through this borehole communications were established with the entombed men and food and candles sent down. A sufficiency of good water was obtainable in the drift and the men remained underground for five-and-a-half days before the water was drained, when they were found to be little, if any, the worse for their imprisonment.

Townhead Mine is 50 fathoms deep and was sunk in 1910. At the time of the accident it was a single shaft mine so far as the main level was concerned. Had the accident occurred a few hours later, when over 50 men would have been in the mine, the loss of life would in all probability have been much more serious.

After a long and exhaustive enquiry before Mr. G. A. L. Skerry, Coroner, into the cause of the death of Bewley, a verdict of "Accidental Death" was returned, and the jury authorised the Coroner to recommend John Cairns for the Edward Medal for the bravery he displayed in returning to warn James Ward. I am pleased to say that Mr. Cairns duly received the Edward Medal of the Second Class in August last.

No breach of statutory regulations was disclosed and a ladder way in the shaft is not compulsory. Three important points however arise out of the occurrence, viz. (a) single shafts ; (b) outlet to a higher level; and (c) plans.

A second outlet would not have saved Bewley's life as he was actually at the shaft. A second shaft sunk to the same level would have afforded additional facilities for the quicker drainage of the water and if sunk to the rise would possibly have enabled Cairns and Ward to escape without delay. An outlet to the shaft at a higher level might have afforded an equally effective means of escape.

With regard to plans, the importance of recording full and accurate information upon plans of abandoned mines is once more emphasized."

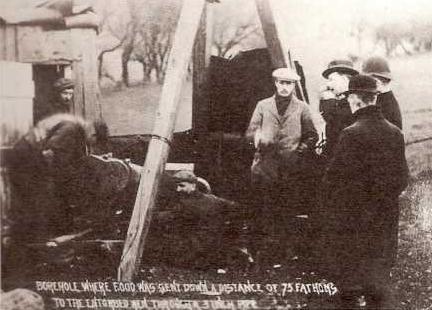

A contemporary photograph showing miners and management officials at the head of the bore whole used to communicate and send provisions down to the two trapped miners in the Townhead Mine disaster of 1913.

In July 1913 John Cairns was duly awarded the Edward Medal (or miner's V.C.) for his actions in the Townhead Mine incident.

It is tempting to think that the gold fob illustrated may have been

presented to John Cairns or James Ward by the mine's workforce or management.

Or alternatively presented to one of the other key personalities in the

associated rescue of the two trapped miners. More research is required to

confirm this. I do not believe that this fob is one from a mass produced

commemorative issue like those known from certain other more serious UK mining

disasters. Although at the time it occurred the Townhead Mine incident

captured the attention of the local population I do not think that it would

have prompted anyone to have commissioned a general commemorative or

fundraising fob issue.

The same month saw the Townhead Mining Company distributing its own medals to

all who helped liberate the two trapped miners. The medals were of gold, and

inscribed with the words "Townhead Mining Company Limited" and the dates March

13th - March 18th. A total of eighty of these medals were issued. It is

most likely that they took the appearance of that picture above (also see

detail below) which was presented to John Cairns and which is still housed in

the same presentation case as his Edward Medal.

As both medals are based on suitably general mining themes and have hallmarks

of 1912, the year before the Townhead incident, it must be concluded that both

types were "off the shelf" items which were only engraved to suit their final

specific purposes.

I do not believe that this is the sort of item that would have been produced

as a keepsake for general sale, these were people on very low incomes and gold

medals would have been out of their reach.

We are now planning to present the fob to the Florence Mine museum in my

grandfather's memory.